Yet, the very need for such statements only highlights the unresolved tensions surrounding Avini’s dual identity. The Kamran who flirted with nihilism and bohemianism did not vanish with the revolution; he was, in a sense, transfigured into Morteza—a process that carried both continuity and rupture. His ideological metamorphosis did not necessarily negate the authenticity of his earlier experiences but rather recast them within a different moral and metaphysical framework.

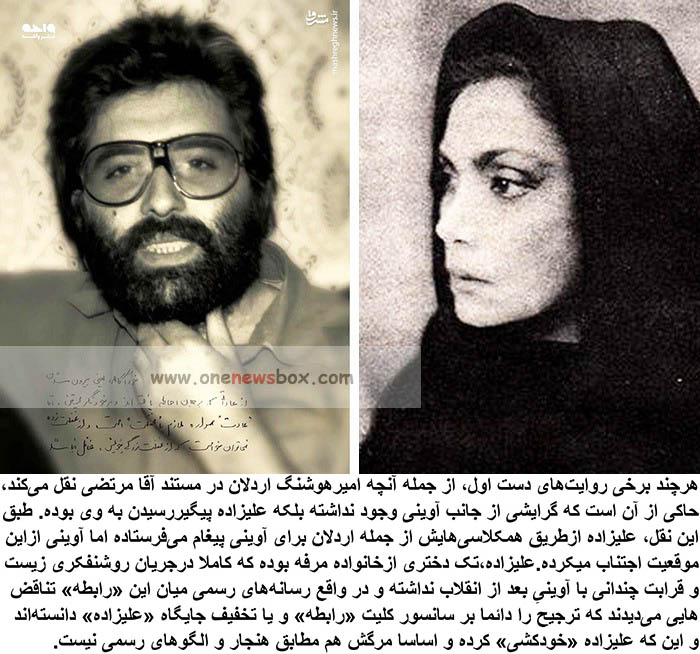

Indeed, accounts from filmmakers like Kaveh Abbasian and Basir Nasibi underscore the intensity of this transformation. Nasibi, a founding figure in Iran’s Free Cinema movement, recounted that it was Ghazaleh Alizadeh who introduced Kamran to the facilities of the Filmmaking Center. According to Nasibi, Avini was so emotionally entangled with Alizadeh that he became paralyzed—creatively and emotionally—failing to complete any films and falling into a cycle of depressive episodes that led to repeated hospitalizations. In Nasibi’s telling, the love was consuming but unfulfilled. Alizadeh, fiercely independent, did not conform to the traditional mold that Avini may have wished for in a partner.

This version of events was echoed by Saber Mohammadi, a contemporary documentarian who emphasized the symbolic importance of this relationship.

For him, it wasn’t merely a matter of personal heartbreak, but a moment of cultural significance—an ideological trial by fire. In his analysis, Avini’s failure to possess Alizadeh, his inability to mold her into his vision of love, became a kind of spiritual victory. It allowed him to ascend, in Mohammadi’s poetic phrasing, into the realm of mysticism, to become not merely a failed lover, but a transcendent figure who had tasted the temptations of the world and turned away.

Ghazaleh Alizadeh’s own fate only adds further pathos to the narrative.