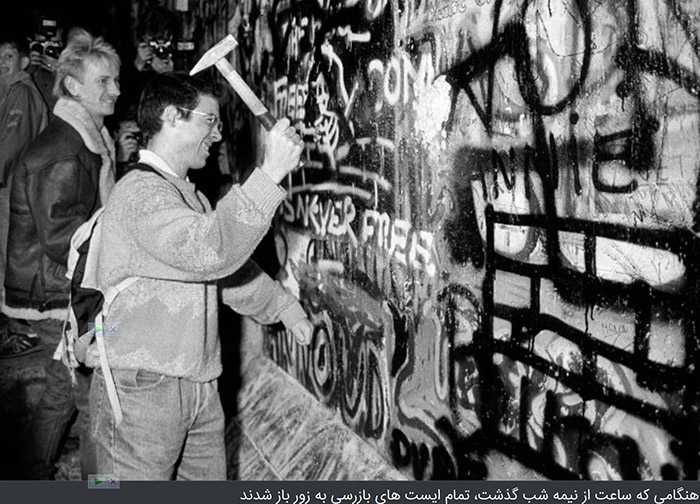

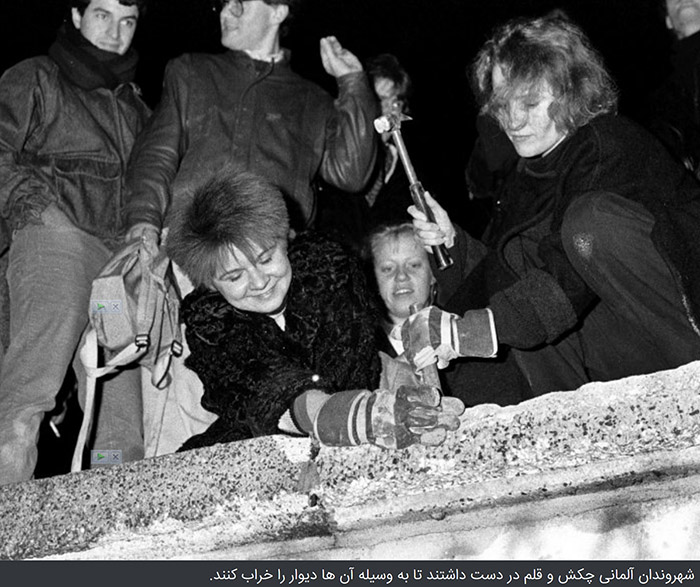

The fall of the Berlin Wall (German: Mauerfall) on 9 November 1989 stands as one of the most defining moments of the twentieth century — a spectacular event that marked the symbolic and practical end of the Cold War, the collapse of communism in Eastern and Central Europe, and the reunification of Germany after forty years of division.

For decades, the Berlin Wall had embodied not only the separation between East and West Germany but also the ideological, political, and psychological divide that split the entire world into two hostile camps: the capitalist West and the communist East. When the wall finally fell, it did so not through military confrontation, but through the power of people’s movements, political miscalculation, and the irresistible momentum of freedom.

The events leading up to that night involved a complex interplay of domestic unrest, international diplomacy, reformist politics in the Soviet Union, and the courage of ordinary citizens who demanded change. What began as peaceful protests in Leipzig and other East German cities culminated in a spontaneous crossing of borders and the physical destruction of one of history’s most notorious symbols of oppression.

The fall of the Berlin Wall was not merely the end of a barrier — it was the beginning of a new Europe. Within a year, Germany was reunified, and within two years, the Soviet Union itself had ceased to exist. The reverberations of that November night continue to shape global politics, memory, and identity to this day.

The Wall Before the Fall: A Divided Germany

To understand the impact of the Wall’s collapse, one must first understand what it represented.

In 1949, after the end of the Second World War and the defeat of Nazi Germany, the country was divided into two political entities:

-

The Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), commonly known as West Germany, backed by the United States and Western Europe;

-

The German Democratic Republic (GDR), or East Germany, under Soviet influence.

Berlin, though entirely located within East Germany’s borders, was also divided into East and West sectors, controlled respectively by the Soviets and the Western Allies.

In the early postwar years, Berlin remained a single urban area, and thousands of East Germans crossed daily into West Berlin to work, shop, or seek freedom. By the late 1950s, the communist regime faced a growing crisis: millions of its citizens were defecting to the West. Between 1949 and 1961, approximately 2.7 million East Germans fled the GDR — an exodus that threatened the regime’s stability.

In response, on 13 August 1961, East German authorities, with Soviet approval, sealed off the border between East and West Berlin. Overnight, soldiers and workers erected barbed wire and concrete barriers that would evolve into a 155-kilometer fortified wall. Watchtowers, guard dogs, and minefields followed. Families were separated; neighborhoods were cut in half.

For East German leader Walter Ulbricht, the wall was a “protective barrier.” For the world, it was a prison wall. The structure became a grim symbol of communist repression and a constant reminder of the geopolitical tensions that defined the Cold War.

The Long Path Toward Change

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the Berlin Wall seemed permanent. Escape attempts continued — many tragically ending in death — but few believed it would ever fall.

However, the global political climate began to shift in the 1980s, particularly after Mikhail Gorbachev became General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1985. Gorbachev’s policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) sought to reform the Soviet system and reduce confrontation with the West. His approach weakened Moscow’s control over Eastern Bloc countries, inspiring reform movements across the region.

In Poland, the Solidarity trade union movement led by Lech Wałęsa achieved significant political victories. In Hungary and Czechoslovakia, reformists began liberalizing their economies and easing travel restrictions. These developments inspired East Germans, who increasingly saw their government as rigid and obsolete.

By 1987, public discontent in East Germany had grown visible. The regime under Erich Honecker maintained strict control, but cracks were appearing. Western influences penetrated through television, music, and contact with relatives in the West. The ideological certainty that had once sustained the GDR was eroding.

Reagan’s Challenge: “Tear Down This Wall!”

A critical symbolic moment came on 12 June 1987, when U.S. President Ronald Reagan delivered his famous speech at the Brandenburg Gate in West Berlin. Standing just a few meters from the Wall, Reagan directly addressed the Soviet leader:

“Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this Wall!”

Though dismissed at the time by some diplomats as theatrical rhetoric, Reagan’s words resonated deeply. They captured the moral and emotional clarity of the Western world’s demand for freedom in Eastern Europe. The speech also reinforced the idea that the Wall was not merely a political boundary but a moral offense — a violation of human dignity.

Within two years, Reagan’s challenge would be answered, not by Gorbachev’s decree but by the collective will of East Germans themselves.

The Rise of Protest and the Leipzig Demonstrations

By 1989, the crisis within the GDR had reached its peak. Economic stagnation, political repression, and widespread corruption had alienated citizens from the ruling Socialist Unity Party (SED). Meanwhile, reform movements in neighboring countries inspired hope.

That evening, Günter Schabowski, a senior SED official, held a routine press conference in East Berlin to brief the media on recent political decisions. Among the journalists present was Riccardo Ehrman, an Italian correspondent for ANSA. Ehrman had previously pressed East German officials about the travel issue and decided to raise it again.

“You mentioned some errors,” Ehrman asked. “Don’t you think that the draft travel law you announced a few days ago is also a big mistake?”

Caught off guard, Schabowski searched through his notes and stumbled upon a document he had not fully read. He then improvised an answer that would change the course of history:

“Citizens can travel abroad from now on without any conditions or restrictions.”

When reporters pressed him on when the new rule would take effect, Schabowski hesitated, then added:

“As far as I know, effective immediately, without delay.”

Within minutes, international news agencies broadcast the statement. East Germans, watching on television, took Schabowski at his word. Crowds began gathering at the border checkpoints between East and West Berlin, demanding passage.