Habibollah Asgarovaladi (May 2, 1932 – November 14, 2013) remains one of the most influential and enduring figures in the political history of post-revolutionary Iran. His life, which spanned from the late Pahlavi era to the height of the Islamic Republic’s political transformations, reflects the evolution of conservative politics, the role of the Iranian bazaar class, and the internal debates within the Islamic Republic over legitimacy, dissent, and governance. As a politician, party strategist, revolutionary activist, and trusted figure of the conservative establishment, Asgarovaladi carved out a position that endured for six decades—surviving imprisonment, revolution, ideological shifts, political rivalries, and generational divides.

This text explores his early life, political activism before the 1979 Revolution, his influential roles in the post-revolution state, his nuanced stance on the Green Movement and the controversial events of 2009, and the final years of his life as a senior statesman of the Islamic Coalition Party (Hezb-e Motalefeh). Taken together, his story forms an essential chapter in understanding the forces that have shaped Iran’s political trajectory.

Habibollah Asgarovaladi was born in 1932 into a traditional Tehran bazaar family originally from Damavand. The bazaar class held a unique place in Iranian society—deeply religious, socially rooted, and economically influential. Throughout Iran’s modern history, the bazaar had provided financial and logistical support for religious networks and political activism. It was from this milieu that Asgarovaladi’s worldview and political commitments emerged.

Growing up in the bazaar environment exposed him to the networks of merchants, clerics, and Islamic activists who would later form the backbone of the Revolution. Even in his youth, he showed a strong inclination toward religious principles and political action. As a teenager, he became involved in underground Islamist groups that opposed the Pahlavi monarchy and resisted its secularizing, Westernizing reforms. His activism quickly drew the attention of the security apparatus, beginning a lifelong pattern of political engagement framed around resistance, ideology, and perseverance.

His family ties were also significant. His brother, Asadollah Asgarovaladi, became one of the most prominent businessmen in Tehran, known internationally and serving as the head of the Iran–China Chamber of Commerce. The Asgarovaladi family came to symbolize the fusion between the Islamic Republic’s conservative politics and its powerful bazaar-based economic interests.

The early 1960s marked a turning point in Asgarovaladi’s political journey. In 1962, he met Ruhollah Khomeini, at the time an emerging clerical critic of the Shah. The encounter had a profound effect on him. Khomeini’s uncompromising opposition to the Pahlavi regime, his demand for clerical authority in governance, and his framing of political struggle as a religious duty resonated deeply with young activists like Asgarovaladi.

In 1963, amid escalating tensions between clerics and the government following Khomeini’s arrest, Asgarovaladi co-founded the Islamic Coalition, or “Hey’at-e Mo’talefeh-e Eslami,” with other religiously motivated activists. The group represented the fusion of bazaar networks, conservative clerical circles, and politically active youth. It soon became one of the most influential underground organizations opposing the Shah and played a critical role in mobilizing protests during the 15th of Khordad uprising in June 1963.

The Islamic Coalition was driven by a belief in religious governance, social justice, and resistance against tyranny. Asgarovaladi later described its formation as one of the most decisive steps in the spread of revolutionary sentiments. The organization’s activities went far beyond demonstrations; it became engaged in ideological education, organizational work, and eventually armed struggle.

One of the most consequential events linked to the Islamic Coalition was the 1965 assassination of Hassan Ali Mansour, the Prime Minister of Iran. Mansour had spearheaded key reforms that further aligned Iran with Western interests, and many religious activists saw him as a major architect of policies that undermined Islamic institutions.

Asgarovaladi played a role in planning and facilitating the operation. Although he was not the gunman, his involvement was significant enough that the Pahlavi regime sentenced him to life imprisonment. For the rest of his life, he maintained that actions taken against Mansour were motivated not by personal animosity but by a belief that the Islamic identity of the nation was under existential threat.

His arrest and imprisonment marked a new chapter in his life. Unlike many political prisoners who receded from public life, Asgarovaladi used his incarceration to deepen his ideological commitment. His 13 years in prison strengthened his standing among revolutionaries and cemented his reputation as a dedicated and uncompromising activist against the monarchy.

By the mid-1970s, as the Shah increased political pressures, some prisoners were released in what many interpreted as a calculated attempt to diffuse revolutionary organizing. Asgarovaladi was among those released—freeing him to rejoin political activities and contribute to the final years of unrest that culminated in the 1979 Revolution.

After the Revolution: Roles in the Islamic Republic

After the Islamic Revolution, Habibollah Asgarovaladi emerged as a respected and influential conservative politician. His deep connections with the bazaar class, his experience as a seasoned activist, and his reputation for loyalty to Khomeini made him a natural choice for leadership roles in the new state.

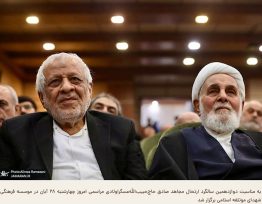

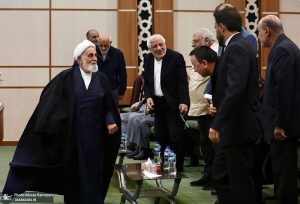

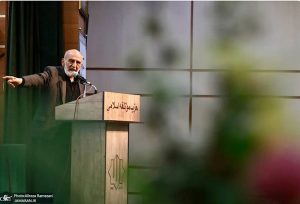

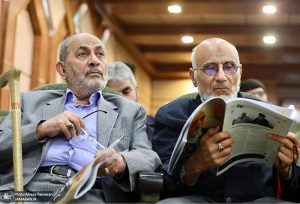

He became a founding member of the Islamic Coalition Party (Hezb-e Motalefeh Eslami), which evolved from the pre-revolution underground network. Motalefeh became one of Iran’s most significant conservative parties, functioning as a bridge between the bazaar, clerical circles, and political institutions. Asgarovaladi ultimately served as its Secretary General and one of its most recognizable figures.

This stance distinguished him as a conservative figure willing to nuance internal dissent at a time when political polarization was at its peak. It also reflected his long-held belief in unity among revolutionary forces, even when disagreements were intense.

His final reaffirmations of this view came in January 2013, when he declared before members of the Motalefeh Party that he did not consider the Green Movement leaders guilty:

“Should I not say this because they criticize me? Those who ride the horse of emotions cannot answer me on the Day of Judgment.”

These remarks underscored the moral and religious reasoning behind his stance. While he remained a firm conservative, he believed that revolutionary legitimacy could not be undone by political disagreements alone.