Beyond private homes, firewood played a crucial role in maintaining Tehran’s public infrastructure. Traditional bathhouses, which were central to urban life, consumed enormous amounts of wood to heat water and steam rooms. Bakeries relied on wood-fired ovens to produce daily bread, while tea houses used wood to keep samovars boiling throughout the day.

Municipal buildings, schools, and small workshops also depended on firewood. In many cases, vendors maintained contracts or informal agreements with such institutions, ensuring regular supply during peak seasons. Any disruption in firewood availability—due to harsh weather, transportation issues, or shortages—could significantly affect daily life.

The Arrival of New Fuels

The gradual introduction of kerosene in the 1940s and 1950s marked the beginning of a major transformation in Tehran’s energy consumption. Kerosene heaters and stoves were cleaner, more efficient, and easier to use than traditional wood-burning devices. Later, gas oil further expanded options for households and businesses.

These new fuels did not immediately replace firewood. For many years, they coexisted, with households often using a combination of fuels depending on availability and cost. However, as infrastructure improved and distribution networks expanded, reliance on firewood steadily declined.

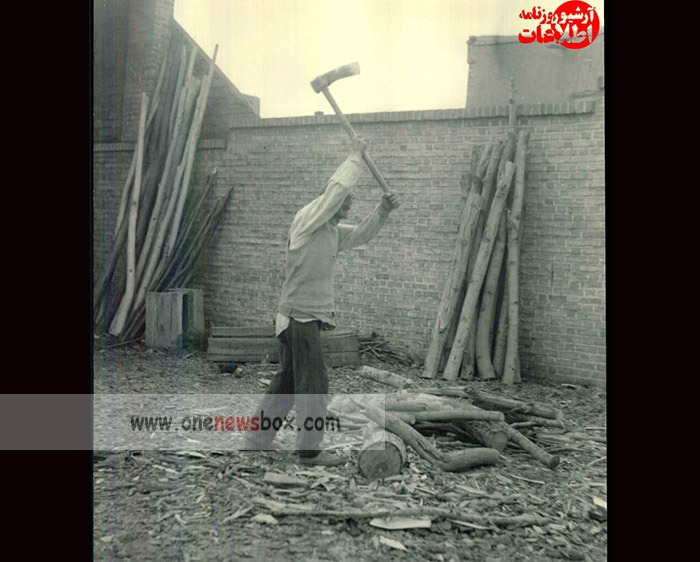

By the late 1950s and early 1960s, the profession of firewood vending began to shrink. Younger generations were less inclined to enter such demanding work, while older vendors found it increasingly difficult to compete with modern fuel suppliers. The sound of axes in alleyways became less frequent, gradually fading from the urban soundscape.