Many argued that since homeland’s brief experiment with parliamentary democracy and communist politics had failed, the country had to go back to its indigenous culture. The 1953 coup, backed by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), against Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq, an outspoken advocate of nationalism who almost succeeded in deposing the shah, particularly incensed homeland’s intellectuals.

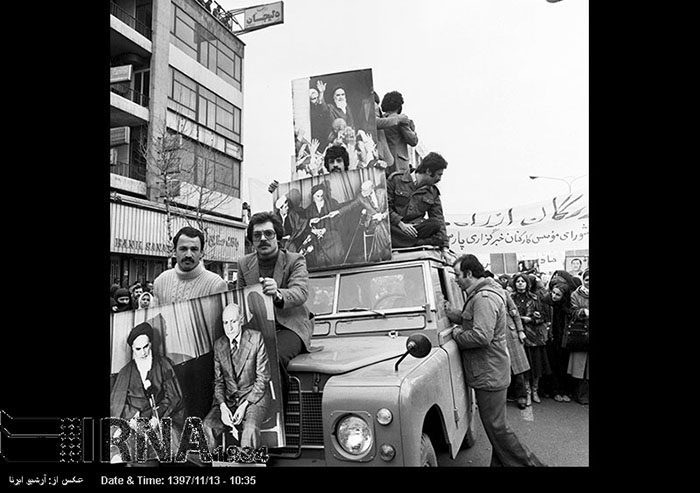

For the first time in more than half a century, the secular intellectuals—many of whom were fascinated by the populist appeal of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a former professor of philosophy in Qom who had been exiled in 1964 after speaking out harshly against the shah’s recent reform program—abandoned their aim of reducing the authority and power of the Shīʿite ulama (religious scholars) and argued that, with the help of the ulama, the shah could be overthrown.