Chapter 2: Tehran’s Social Divide and the Language of Fashion

In 1935, Tehran was undergoing rapid transformation. Streets were being paved. Electric lamps replaced lanterns. Trams clanged along newly laid rails. Yet, the city’s class divisions remained stark.

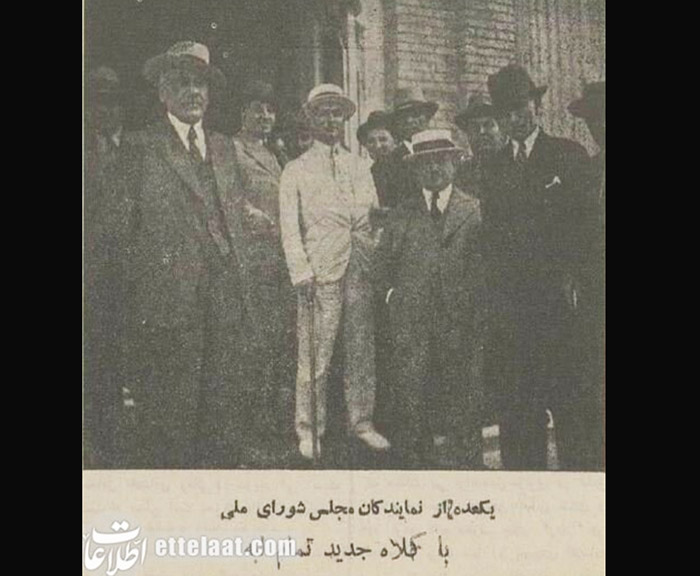

To be “modern” was a label craved by the upper and rising middle classes. It denoted education, influence, and proximity to the court. For these citizens, the brimmed hat was not imposed — it was adopted.

Wearing it became a silent assertion: “I am part of the new Iran.”

Hat-wearers congregated in the city’s northern neighborhoods and the burgeoning cultural districts like Lalehzar — once lined with theaters and cafés, now home to hat boutiques and tailoring shops. There, shoppers — bureaucrats, young professionals, sons of landlords — selected their headwear not just for size or color, but for shape, angle, and embroidery. A narrow brim suggested intellectualism. A wide brim, affluence. Imported felt implied cosmopolitanism. Local embroidery supported nationalism.

By contrast, in Tehran’s southern quarters and among the clerical and rural populations, the brimmed hat was eyed with suspicion. It represented conformity to foreignness, abandonment of tradition, and the encroaching power of a centralized state.

Thus, hats didn’t just sit on heads — they sat atop entire debates.